InfoGuard AG (Headquarter)

Lindenstrasse 10

6340 Baar

Switzerland

InfoGuard AG

Stauffacherstrasse 141

3014 Bern

Switzerland

InfoGuard Deutschland GmbH

Frankfurter Straße 233

63263 Neu-Isenburg

Germany

InfoGuard Deutschland GmbH

Landsberger Straße 302

80687 Munich

Germany

InfoGuard Deutschland GmbH

Am Gierath 20A

40885 Ratingen

Germany

InfoGuard GmbH

Kohlmarkt 8-10

1010 Vienna

Austria

Advent, Advent, the school is “burning”! [Part 3]

In the second part of our cyber Advent story we found out that attackers make mistakes too. Sometimes they select and encrypt targets that don’t really have much money to spend. In the third and final part of our story, you will learn how the ransomware attack played out.

At Winterstadt School, we discovered that the initial attacks were already taking place back in the spring, and they continued over the summer. We suspected that various threat actors were prowling around on the systems (activities like port scans, lateral movement, installation of remote access solutions like AnyDesk, etc.). Most of the cyber criminals seem to have realised that this was a state school and therefore left it alone. Why then go to all that trouble when there are more lucrative targets? Presumably, this access was then sold on to someone else on the Darknet, so that at least the work they had done would make some kind of profit. This is where our attackers came in. They had done their research badly and assumed that they could demand a ransom, and encrypted the systems.

Cyber criminals also value their reputations

Back to the status quo. In the meantime, the attackers had grasped that there was probably not much money to be made here. Once again, this revealed that the majority of ransomware attacks are not targeted, they are pretty opportunistic – wherever they can get in, they encrypt. This is a very important point in what is called “threat modelling”. This process involves a company validating and constructing its security system based on the likelihood of an attack by a certain grouping. I frequently hear statements like: “We have to protect ourselves against Nation State or against targeted industrial espionage.” However, the most likely form of attack for most companies remains opportunistic ransomware attacks. The probability of this occurring is very high, causing maximum damage.

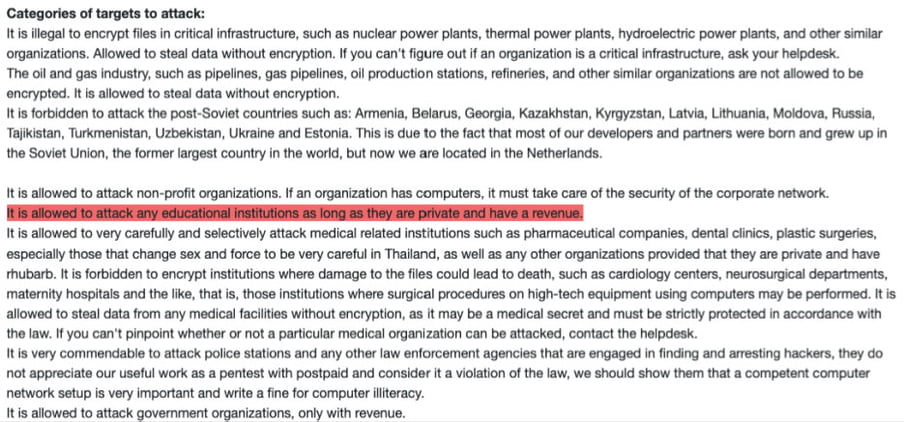

So for us, most of the investigation was already over and done with; it was not even an option to pay the ransom. This is always the point where we structure the negotiations in such a way that we always maintain an exit strategy, while negotiating more aggressively over the price or even daring to pull a stunt. “LockBit” perceives itself as a serious business with a very strong reputation. If I wanted to “sign up” as a LockBit affiliate, I would have to fulfil various requirements. For example, I have to advance a sum of money corresponding to one Bitcoin (currently around 15,000 Swiss francs), and I have to be known or recommended in hacker forums. In addition, there are the so-called “Affiliate Rules” that you need to adhere to:

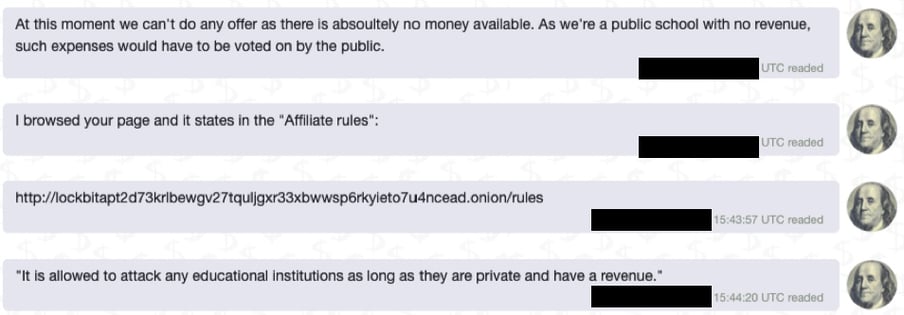

To put pressure on the attackers, we used the fact that educational institutions are only allowed to be encrypted if they are not state schools and they generate revenue.

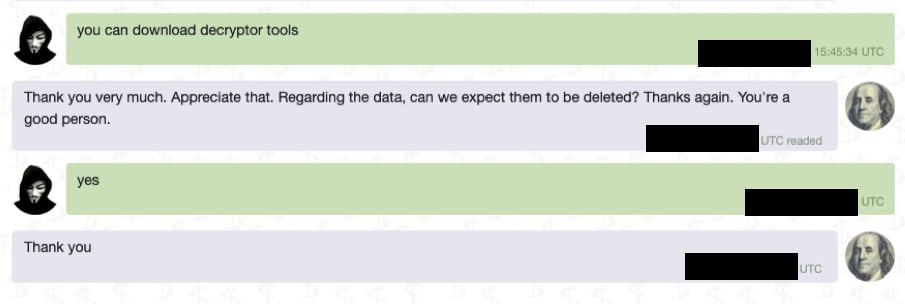

In the end, I don’t know for sure what the crucial turning point was, whether it was the fear of having broken the rules, or simply the realisation that all the work was not worth it, but the reaction was immediate (see time stamp):

The decrypter we received afterwards definitely worked, and the teachers’ missing home drives could also be recovered, and most importantly, no data was published.

Who knows, perhaps the attackers remembered that there was such a thing as morals and ethics after all when they released the data. In any case, the hopeful romantic in me would really love to believe that...

In this spirit, my team and all my InfoGuard colleagues and I would like to wish you and your nearest and dearest a festive and “safe” Christmas time!

Blog

Neue Microsoft 365 E7 Frontier Suite: Was CISOs jetzt wissen müssen

InfoGuard Threat Intelligence Report Q1/26: Geopolitische Cyberlage Europas nach «Epic Fury»