Career 15 Vacancies 250+ Employees

Career 15 Vacancies 250+ Employees

InfoGuard AG (Headquarter)

Lindenstrasse 10

6340 Baar

Switzerland

InfoGuard AG

Stauffacherstrasse 141

3014 Bern

Switzerland

InfoGuard Deutschland GmbH

Landsberger Straße 302

80687 Munich

Germany

The way to the cloud is paved with a few pitfalls [Part 1]

Clouds – or rather cloud-based IT services of infrastructures (IaaS), platforms (PaaS) and software (SaaS) – have definitely arrived in the business environment. What's more, in the coming years services will increasingly be offered exclusively cloud-based. A significant portion of today's on-premises IT services will be migrated to the cloud. Companies should therefore be prepared to take this step in good time. But what is the secure route to the cloud? In the first part of our two-part blog serie, we provide you with general thoughts on cloud vendors, models, architectures and responsibilities. In the second part, you'll get practical tips for making your cloud environments secure.

Think about the right shape for your cloud

Let’s get straight to the point – there is no such thing as “the” cloud. Already today, many businesses are more or less knowingly using cloud services from a variety of providers. Any service that is not operated by the company itself and that is available via the Internet is almost certainly a cloud service. Procurement processes are not standardised and formalised in the same way everywhere, and this can quickly lead to proliferating cloud use within a company. This means that you can quickly lose track of which applications are actually in use. You can find out about the risks involved in working like this in a previous article.

Multi-cloud versus hybrid-cloud

Using multiple cloud providers at the same time is called “multi-cloud”, as not all services are purchased exclusively from one single provider. This should not be confused with the “hybrid-cloud” architecture model, where there is a mixture of different service and operating models. For example, the infrastructure can be obtained from a provider as an IaaS service. The same infrastructure is partially self-operated and partially used as a back-end for PaaS or SaaS services from another provider. The most important feature of a hybrid-cloud is the mixture of on-premises and public-cloud (off-premises) services. This invariably leads to the next issue – the architecture of the cloud. After (hopefully) having thought about the most suitable service and architecture model (public, private, community, and hybrid), you need to define the cloud architecture.

Defining an appropriate cloud architecture

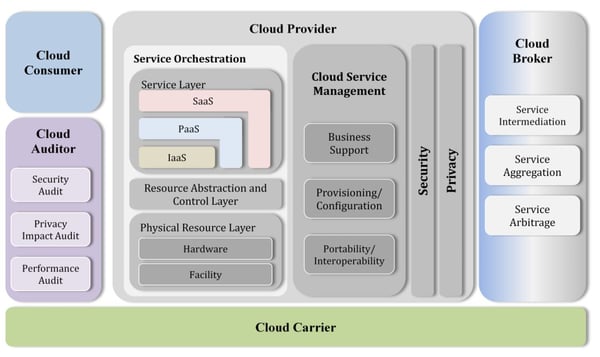

The NIST (National Institute of Standards & Technology) reference architecture can be a good tool for defining the top-down architecture. In general, it's important to define which cloud service providers, technologies and services are managed for which module with which controls. To put it another way:

- When it comes to security: do you have comprehensive knowledge of every element in the reference architecture in all its forms and at all times?

- Which services does the cloud service provider (CSP) actually offer, how are they obtained and who's responsible for which part?

- What exactly do the various certifications and attestations that the CSP has submitted mean?

- What does the (security) reporting and the (detailed) service architecture look like?

- What purpose should the various cloud services serve – for internal use within the company or for publicly available services?

- Who and where are the cloud consumers (users)?

- How is identity and access management resolved and possible federations designed?

- At what times and from what locations are the cloud services used?

- Which cloud auditors perform which audits, how often and for which services?

- What's “in scope” or “out of scope” in an inspection / audit, and which parts of the service and the underlying systems and infrastructure have actually been audited? This is stated in an audit report and should be carefully verified.

Cloud broker versus cloud carrier

Bundling, re-labelling and reselling cloud services – in a nutshell, this is what cloud brokers do. NIST describes cloud brokers as acting as the intermediary between the two parties: cloud users and service providers. The cloud broker performs a variety of roles. Particularly small and medium-sized companies that cannot or do not want to purchase cloud services directly from a large provider rely on offers from cloud brokers. Responsibilities must be clearly defined, in particular for operations and any changes to or withdrawal from a cloud service.

Figure 1 – NIST cloud computing reference architecture

In short, cloud carriers – which in our experience is a term that is used less often – offer network services (e.g. transmission capacity, (leased) lines and content delivery networks (CDN)). However, in some cases, the services are offered as a service by the CSP itself, without there being a specific / separate cloud carrier. It should be noted that very often these services are not globally available in all countries. Often the communication between the on-premises endpoints and the cloud services can and must be planned and designed with the desired performance in mind and using dedicated connections. People often forget this point. When cloud services are used on a large scale, ideally the capacity of the connections is better than “best-effort” on the part of the Internet service provider and the cloud carrier.

Decide on the right cloud service model

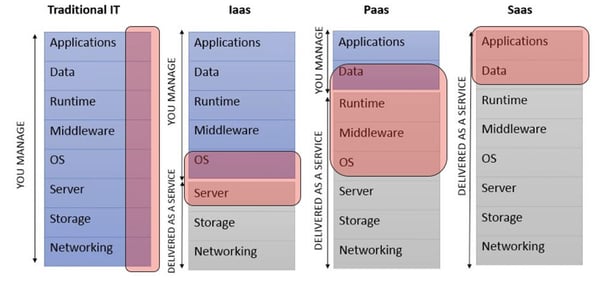

With the various service models, as with software and application security, the problem is actually the interface and the associated change in responsibilities. Compared to “traditional in-house IT”, with XaaS you only control part of the service at a time – you are reliant on the cloud service provider for the rest. It's worthwhile underpinning this trust relationship with formal specifications and paying close attention to what is in the GTC (General Terms and Conditions), and which services are included and excluded. Nasty surprises in this area often have the potential to degenerate into genuine security vulnerabilities.

The choice of service models has an impact on responsibility

To visualise the responsibilities (and pitfalls), the following diagram compares the different models. The areas coloured red represent the interfaces / handover points of responsibility which you should focus on during implementation:

Figure 2 – Service models and responsibilities at a glance

The providers or cloud service providers often use different terms for the interfaces and the services running below or above them, which are not always precisely specified. Therefore, you should ensure that these have been clearly explained, along with who is responsible for what. Besides, it's good to know who is “also” responsible. In other words, for example, if the CSP is responsible for patching the operating system but not for configuration and hardening – what access rights does the cloud service provider have for this purpose? As a result, can the CSP carry out other activities or functions than those that are actually necessary for security patching?

When choosing a cloud provider, don’t forget the “small print”

Cloud services are often likened to outsourcing, but there are some important differences. In general, CSPs rely heavily on standardisation and automation to develop and operate services economically. Legally, this affects the relationship between the supplier and the customer, in that the contracts are not individual agreements, they are General Terms and Conditions. This means that individual adjustments and agreements are neither desirable nor possible.

Cloud services are also usually based on the “supply and demand principle”. The CSP offers specific, specified and standardised services. On this basis, customers can obtain the right service for them. There is no individual customisation taking place. If the offer does not fit the customer's needs, they have to look for another provider or seek some other kind of help. This means that the CSP's service level, the technologies used, change and release management, price models, contractual conditions and support options are standardised, and at best they can only be negotiated within a narrow framework – or rather, made up of different variants and modules.

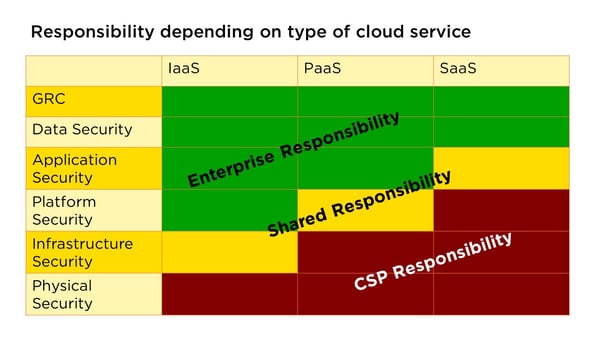

Defining responsibilities and accountabilities

Once you have found the right partner, you need to define responsibilities. Please bear in mind that responsibility cannot be delegated – but fulfilling a task can be. The following diagram shows how the responsibilities are allocated in the various service models:

Figure 3

Ultimately, it's always the customer – for instance you – who is responsible for the overall supervision and control, i.e. the governance of the service they have purchased, and this cannot be delegated. Likewise, the customer is responsible for the data as its owner. The advantage for the CSP is that it cannot be held liable for the security of the data (contents) to the fullest extent (beyond a duty of care). In terms of data protection this is quite reasonable, because otherwise, the provider would potentially be able to gain rights as a result of (co-)ownership of the data. Furthermore, these legal issues and implications are by no means trivial, which is why it would be wise to do a detailed analysis of the contractual arrangements for compliance with the requirements of the law on obligations, data protection and other legal requirements. If you don't have any in-house lawyers, we recommend you to consult an independent expert.

As already explained in the previous section on interfaces, “shared responsibility” should be specified and demarcated as precisely as possible. The responsibility for physical security essentially lies with the CSP, as even with an IaaS service model, the hardware is only rented and there is often no direct (physical) access to the systems.

Data lifecycle and the cloud

To maintain an overview between service and architecture models and especially between multi- and hybrid-clouds it helps to structure the lifecycle of business-related data along the lifecycle phases. The graphic (on the right) shows the lifecycle of data in a business process. For each business process or broken down into individual use cases, you should specify exactly where, how, with which tools and in which cloud services the data is processed in the individual lifecycle phases. This is because, from the creation to the destruction of the data, you are responsible for its security!

To maintain an overview between service and architecture models and especially between multi- and hybrid-clouds it helps to structure the lifecycle of business-related data along the lifecycle phases. The graphic (on the right) shows the lifecycle of data in a business process. For each business process or broken down into individual use cases, you should specify exactly where, how, with which tools and in which cloud services the data is processed in the individual lifecycle phases. This is because, from the creation to the destruction of the data, you are responsible for its security!

As you can see, there's quite a lot to consider when it comes to secure migration to the cloud. Use the points given above as a checklist and go through them point by point. The second part of this article, which will be online shortly, also explains what you need to look out for when implementing your cloud environment to ensure that you give equal attention to business requirements and security.

You don't wanna miss an article? Subscribe to our blog updates. That way you will always conveniently receive the latest articles in your inbox.

By the way, you will find many more blog articles on our cyber security blog that deal with cloud security!

Source of figures:

- Figure 1 – NIST Cloud Computing Reference Architecture:

https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/Legacy/SP/nistspecialpublication500-292.pdf - Figure 2– Own illustration; based on various known models

- Figure 3 – Own illustration

- Figure 4 – Own illustration; based on https://roaringelephant.org/2019/01/15/episode-123-infrastructure-and-data-lifecycle-part-2/

Blog

Incident Response Planning (IRP): Gut vorbereitet, stark im Ernstfall

Zero Trust Maturity Model 2.0: Reifegradmodell auf 5 strategischen Säulen